207x Filetype PDF File size 0.09 MB Source: edwardseducationblog.files.wordpress.com

Historical method 1

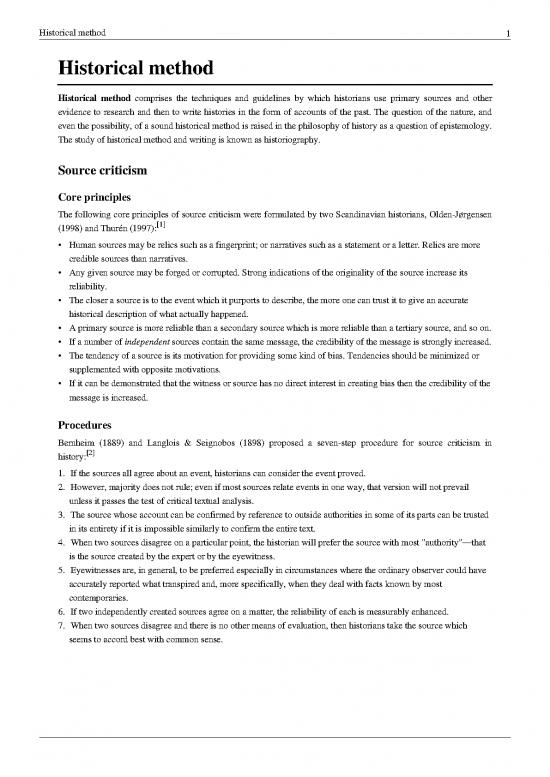

Historical method

Historical method comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other

evidence to research and then to write histories in the form of accounts of the past. The question of the nature, and

even the possibility, of a sound historical method is raised in the philosophy of history as a question of epistemology.

The study of historical method and writing is known as historiography.

Source criticism

Core principles

The following core principles of source criticism were formulated by two Scandinavian historians, Olden-Jørgensen

(1998) and Thurén (1997):[1]

• Human sources may be relics such as a fingerprint; or narratives such as a statement or a letter. Relics are more

credible sources than narratives.

•• Any given source may be forged or corrupted. Strong indications of the originality of the source increase its

reliability.

•• The closer a source is to the event which it purports to describe, the more one can trust it to give an accurate

historical description of what actually happened.

• A primary source is more reliable than a secondary source which is more reliable than a tertiary source, and so on.

• If a number of independent sources contain the same message, the credibility of the message is strongly increased.

•• The tendency of a source is its motivation for providing some kind of bias. Tendencies should be minimized or

supplemented with opposite motivations.

•• If it can be demonstrated that the witness or source has no direct interest in creating bias then the credibility of the

message is increased.

Procedures

Bernheim (1889) and Langlois & Seignobos (1898) proposed a seven-step procedure for source criticism in

[2]

history:

1. If the sources all agree about an event, historians can consider the event proved.

2. However, majority does not rule; even if most sources relate events in one way, that version will not prevail

unless it passes the test of critical textual analysis.

33.. The source whose account can be confirmed by reference to outside authorities in some of its parts can be trusted

in its entirety if it is impossible similarly to confirm the entire text.

4. When two sources disagree on a particular point, the historian will prefer the source with most "authority"—that

is the source created by the expert or by the eyewitness.

55.. Eyewitnesses are, in general, to be preferred especially in circumstances where the ordinary observer could have

accurately reported what transpired and, more specifically, when they deal with facts known by most

contemporaries.

66.. If two independently created sources agree on a matter, the reliability of each is measurably enhanced.

77.. When two sources disagree and there is no other means of evaluation, then historians take the source which

seems to accord best with common sense.

Historical method 2

External criticism: authenticity and provenance

Garraghan divides criticism into six inquiries[3]

1. When was the source, written or unwritten, produced (date)?

2. Where was it produced (localization)?

3. By whom was it produced (authorship)?

4. From what pre-existing material was it produced (analysis)?

5. In what original form was it produced (integrity)?

6. What is the evidential value of its contents (credibility)?

The first four are known as higher criticism; the fifth, lower criticism; and, together, external criticism. The sixth and

final inquiry about a source is called internal criticism.

R. J. Shafer on external criticism: "It sometimes is said that its function is negative, merely saving us from using

false evidence; whereas internal criticism has the positive function of telling us how to use authenticated

evidence."[4]

Internal criticism: historical reliability

Noting that few documents are accepted as completely reliable, Louis Gottschalk sets down the general rule, "for

each particular of a document the process of establishing credibility should be separately undertaken regardless of

the general credibility of the author." An author's trustworthiness in the main may establish a background probability

for the consideration of each statement, but each piece of evidence extracted must be weighed individually.

Eyewitness evidence

R. J. Shafer offers this checklist for evaluating eyewitness testimony:[5]

11.. Is the real meaning of the statement different from its literal meaning? Are words used in senses not employed

today? Is the statement meant to be ironic (i.e., mean other than it says)?

2. How well could the author observe the thing he reports? Were his senses equal to the observation? Was his

physical location suitable to sight, hearing, touch? Did he have the proper social ability to observe: did he

understand the language, have other expertise required (e.g., law, military); was he not being intimidated by his

wife or the secret police?

3. How did the author report?, and what was his ability to do so?

1. Regarding his ability to report, was he biased? Did he have proper time for reporting? Proper place for

reporting? Adequate recording instruments?

2. When did he report in relation to his observation? Soon? Much later? Fifty years is much later as most

eyewitnesses are dead and those who remain may have forgotten relevant material.

3. What was the author's intention in reporting? For whom did he report? Would that audience be likely to

require or suggest distortion to the author?

44.. Are there additional clues to intended veracity? Was he indifferent on the subject reported, thus probably not

intending distortion? Did he make statements damaging to himself, thus probably not seeking to distort? Did

he give incidental or casual information, almost certainly not intended to mislead?

4. Do his statements seem inherently improbable: e.g., contrary to human nature, or in conflict with what we know?

55.. Remember that some types of information are easier to observe and report on than others.

66.. Are there inner contradictions in the document?

Louis Gottschalk adds an additional consideration: "Even when the fact in question may not be well-known, certain

kinds of statements are both incidental and probable to such a degree that error or falsehood seems unlikely. If an

ancient inscription on a road tells us that a certain proconsul built that road while Augustus was princeps, it may be

doubted without further corroboration that that proconsul really built the road, but would be harder to doubt that the

Historical method 3

road was built during the principate of Augustus. If an advertisement informs readers that 'A and B Coffee may be

bought at any reliable grocer's at the unusual price of fifty cents a pound,' all the inferences of the advertisement may

well be doubted without corroboration except that there is a brand of coffee on the market called 'A and B

[6]

Coffee.'"

Indirect witnesses

Garraghan says that most information comes from "indirect witnesses," people who were not present on the scene

[7]

but heard of the events from someone else. Gottschalk says that a historian may sometimes use hearsay evidence.

He writes, "In cases where he uses secondary witnesses, however, he does not rely upon them fully. On the contrary,

he asks: (1) On whose primary testimony does the secondary witness base his statements? (2) Did the secondary

witness accurately report the primary testimony as a whole? (3) If not, in what details did he accurately report the

primary testimony? Satisfactory answers to the second and third questions may provide the historian with the whole

or the gist of the primary testimony upon which the secondary witness may be his only means of knowledge. In such

cases the secondary source is the historian's 'original' source, in the sense of being the 'origin' of his knowledge.

Insofar as this 'original' source is an accurate report of primary testimony, he tests its credibility as he would that of

the primary testimony itself."[8]

Oral tradition

Gilbert Garraghan maintains that oral tradition may be accepted if it satisfies either two "broad conditions" or six

"particular conditions", as follows:[9]

1. Broad conditions stated.

11.. The tradition should be supported by an unbroken series of witnesses, reaching from the immediate and first

reporter of the fact to the living mediate witness from whom we take it up, or to the one who was the first to

commit it to writing.

22.. There should be several parallel and independent series of witnesses testifying to the fact in question.

2. Particular conditions formulated.

11.. The tradition must report a public event of importance, such as would necessarily be known directly to a great

number of persons.

22.. The tradition must have been generally believed, at least for a definite period of time.

33.. During that definite period it must have gone without protest, even from persons interested in denying it.

44.. The tradition must be one of relatively limited duration. [Elsewhere, Garraghan suggests a maximum limit of

150 years, at least in cultures that excel in oral remembrance.]

55.. The critical spirit must have been sufficiently developed while the tradition lasted, and the necessary means of

critical investigation must have been at hand.

6. Critical-minded persons who would surely have challenged the tradition — had they considered it false —

must have made no such challenge.

Other methods of verifying oral tradition may exist, such as comparison with the evidence of archaeological remains.

More recent evidence concerning the potential reliability or unreliability of oral tradition has come out of fieldwork

[10]

in West Africa and Eastern Europe.

Historical method 4

Synthesis: historical reasoning

Once individual pieces of information have been assessed in context, hypotheses can be formed and established by

historical reasoning.

Argument to the best explanation

C. Behan McCullagh lays down seven conditions for a successful argument to the best explanation:[11]

1. The statement, together with other statements already held to be true, must imply yet other statements describing

present, observable data. (We will henceforth call the first statement 'the hypothesis', and the statements

describing observable data, 'observation statements'.)

2. The hypothesis must be of greater explanatory scope than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same

subject; that is, it must imply a greater variety of observation statements.

3. The hypothesis must be of greater explanatory power than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same

subject; that is, it must make the observation statements it implies more probable than any other.

4. The hypothesis must be more plausible than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it

must be implied to some degree by a greater variety of accepted truths than any other, and be implied more

strongly than any other; and its probable negation must be implied by fewer beliefs, and implied less strongly than

any other.

5. The hypothesis must be less ad hoc than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject; that is, it

must include fewer new suppositions about the past which are not already implied to some extent by existing

beliefs.

6. It must be disconfirmed by fewer accepted beliefs than any other incompatible hypothesis about the same subject;

that is, when conjoined with accepted truths it must imply fewer observation statements and other statements

which are believed to be false.

77.. It must exceed other incompatible hypotheses about the same subject by so much, in characteristics 2 to 6, that

there is little chance of an incompatible hypothesis, after further investigation, soon exceeding it in these respects.

McCullagh sums up, "if the scope and strength of an explanation are very great, so that it explains a large number

[12]

and variety of facts, many more than any competing explanation, then it is likely to be true."

Statistical inference

McCullagh states this form of argument as follows:[13]

1. There is probability (of the degree p ) that whatever is an A is a B.

1

2. It is probable (to the degree p ) that this is an A.

2

3. Therefore (relative to these premises) it is probable (to the degree p × p ) that this is a B.

[14] 1 2

McCullagh gives this example:

1. In thousands of cases, the letters V.S.L.M. appearing at the end of a Latin inscription on a tombstone stand for

Votum Solvit Libens Merito.

22.. From all appearances the letters V.S.L.M. are on this tombstone at the end of a Latin inscription.

3. Therefore these letters on this tombstone stand for '’Votum Solvit Libens Merito’’.

This is a syllogism in probabilistic form, making use of a generalization formed by induction from numerous

examples (as the first premise).

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.